If it’s been years since you set foot inside a college classroom, you might be surprised to find that, sometimes in this new era of learning, they’re empty. The students aren’t cutting class. Instead, they’ve turned the community into their classroom. Teaching and learning are no longer cloistered behind ivy-covered campus walls.

A wealth of research confirms that not everyone learns the same way. Some students excel when the professor, perched behind the podium, delivers course content from the front of the classroom. But other students thrive under non-traditional modes of instruction. Recognizing that the best teaching targets a wide variety of learning styles, universities are increasingly investing in new strategies for delivering course content. Institutions now offer online and hybrid courses; immersive learning opportunities in foreign countries; collaborative research ventures involving students and industry leaders; and internship programs, to name a few.

This week, University of North Carolina System President Margaret Spellings has delivered a State of the University address at two regional institutions: Fayetteville State University and UNC Pembroke. Her appearances provide an opportunity to shine the spotlight on one of these non-traditional approaches to teaching: service-learning.

While other, high-tech innovations in the classroom may garner more media attention, the often-unsung service-learning approach to teaching has a remarkably broad impact. This impact doesn’t just benefit the students who absorb marketable skills along the way; it also reaches North Carolina’s underserved residents, who benefit from the energy, leadership, and creativity that students bring into the community.

SERVICE AND LEARNING: IT’S NOT CHARITY

At first glance, the concept of service-learning might seem fairly self-explanatory: universities partner with community organizations and non-profits, giving students resume-building opportunities and life lessons on the importance of civic engagement.

But educators are quick to point out that service-learning is a hyphenated phrase, indicating its dual approach to teaching. Service-learning is not equivalent to charity.

“Service-learning is a teaching strategy that implements the curriculum. [It requires] meaningful service…”

“Service-learning is a teaching strategy that implements the curriculum. [It requires] meaningful service in relation to what’s going on in the classroom, and it also involves critical reflection,” says Sandy Jacobs, UNCP’s associate director for service-learning.

In other words, the service isn’t an end unto itself. It provides students an opportunity to master course content by putting theory into practice. Through hands-on learning, they acquire hard and soft skills that will make them competitive in the modern economy.

By combining theory and practice, service-learning can help students recognize the transferable skills nestled within academic content, even in courses outside their chosen major. Dr. Scott Hicks builds service-learning assignments into his literature, first-year composition, and first-year seminar courses at UNCP:

“I know that in the professional world outside of college, students are going to need to be able to problem-solve and share their findings with others. So students in first-year composition design their own service-learning projects, projects that often include collaborating alongside professionals in their future career field, experiences that give them a richer sense of their research beyond what’s in the sources they find in the library.”

Students famously complain that first-year writing courses are irrelevant to their majors, but Hicks’ approach helps them connect the dots between the university’s general education requirements and the students’ own long-term career goals.

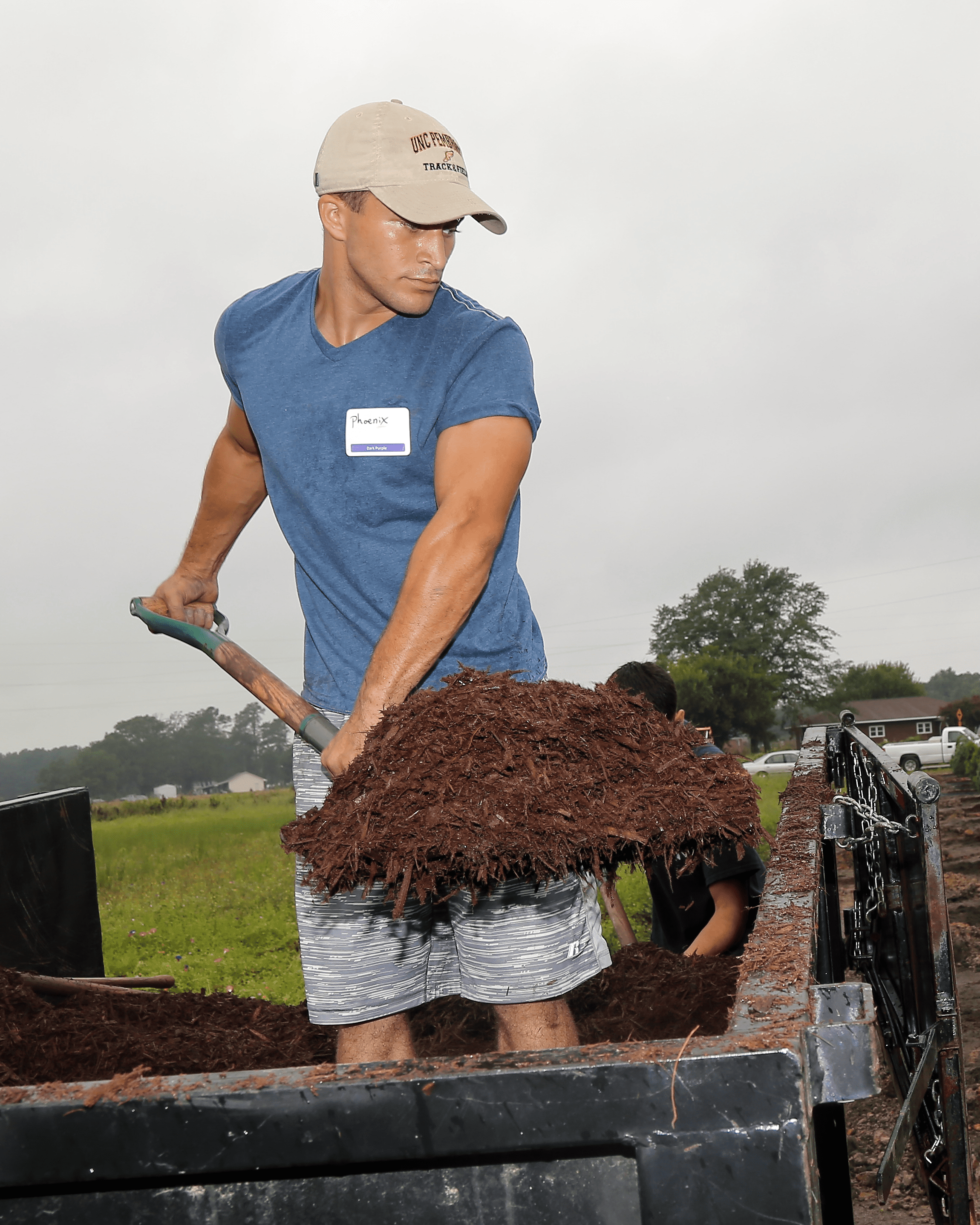

Service-learning courses aren’t just the domain of humanist arts courses either. Many of UNCP’s STEM courses include a service-learning component. In support of the Lumbee tribe’s efforts to transform an abandoned property into a multi-purpose cultural center, environmental science students have tested soil and offered horticultural advice on which plants would thrive in the environment. Biology students have helped identify plant species growing on the center’s nature trail. One professor has ambitions to work with students to establish a bee hive on the property and plans to distribute the honey to local housing authorities.

To ensure that students actually absorb the lessons they learn in the field, service-learning courses typically involve some kind of critical reflection, either in the form of classroom discussion or end-of-semester papers. This final stage of the service-learning process is crucial because it requires students to articulate how their practice in the field connects with the theoretical content covered in course lectures.

Studies show that service-learning opportunities significantly improve student retention rates. In effect, this means that a service-learning experience can actually improve a student’s odds at achieving economic mobility.

BRIDGING THE TOWN VS. GOWN DIVIDE

The UNC System’s support for service learning initiatives is one way the University fulfills its mission to benefit all North Carolinians, not just the students who attend classes. In her ongoing State of the University Tour, President Spellings has been reiterating the important role the UNC System plays in promoting the public good.

FSU’s Office of Civic Engagement and Service Learning’s mission statement makes it clear how service learning is one mechanism for helping the University as a whole accomplish this goal. According to the office’s mission statement, its primary function is to “promote ethical and social responsibility and university engagement that provides public service and outreach.”

FSU’s service-learning and civic engagement initiatives offer some perspective on the impact a single institution can have on a region. It has forged partnerships with veterans’ associations, shelters for victims of domestic violence, health clinics, food banks, museums, and adult care centers. In total, FSU has established over 100 working partnerships with regional organizations and non-profits.

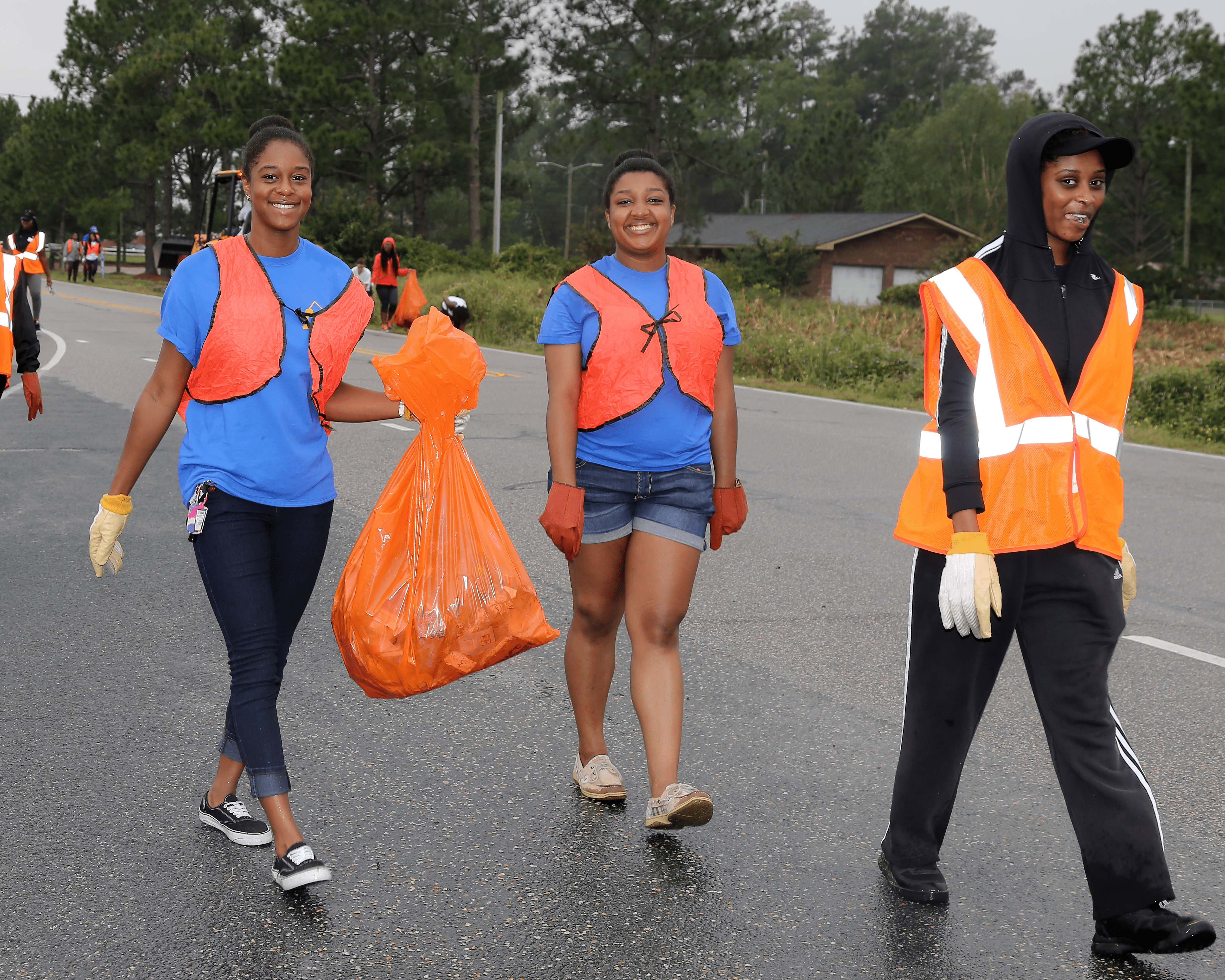

Between 2009–when service-learning was officially introduced into FSU’s curricula–and 2017, students logged more than 100,000 hours of community service. Such efforts provide concrete examples of the University’s positive impact, which extends across the state.

During her appearance at FSU this week, President Spellings expressed how “public institutions are an ally in the effort to make a better world. That public service is honorable and effective. That trust in our fellow citizens, and faith in the country that unites us, is vital to any vision of real progress.”

This outreach is critically important in rural counties, which lag economically. For example, in the Lumber River region where UNCP is located, nearly three out of ten people live below the poverty line. In an area with a poverty rate nearly twice as high as that of Wake and Mecklenburg counties, service-learning courses can have a particularly dramatic impact.

Service-learning courses also have the potential to produce more intangible benefits. More and more frequently, teachers design their critical reflection assignments so that students look beyond their own personal experience; instead, they explore the social and economic circumstances that have left members of their community disenfranchised. This critical engagement with the systemic, root causes of social problems helps transform service learners into community leaders, positioned to take the lead devising long term solutions.

Frequently, the members of the community whom the students serve also learn something along with the students. A major project for Dr. Jane Haladay’s Native American literature course at UNCP revolves around the students helping third graders write their own memoirs. After spending a semester studying the ways indigenous stories explore “Native peoples’ connections to their homelands,” these college students help budding young authors write about a space “that has been an important part of their family, cultural identity, and/or community … and discuss why it is important to protect their special place from harm.” As they guide the third graders through the writing process, Haladay’s students digest and translate course material into their own lesson plans. In addition to discovering the writing process, these third graders are, in all likelihood, starting down a pathway toward their own university education.

At the end of the semester, Haladay’s students compile these stories and print them in booklets, which are distributed to the third graders who wrote them. The image of these young authors holding the end result of their own creative energies in their hands serves as a fitting metaphor for what service learning can accomplish. Through the University’s organized engagement with the community, knowledge is created and shared, students progress academically and professionally, and North Carolinians can witness some of the tangible results of public investment in the UNC System.